In family history research, there are days where we make great headway – like the stars suddenly align, and new branches of our tree just sprout out. But most of the time, we may feel stuck staring at our brick walls waiting for a brick to move.

In 2018 and 2019, I wrote about ways that I have been working on my Williams family brick wall: making sure I have a solid base of research with vital records and census records, then by using marriage and church records, descendancy and DNA research, and then combing personal property and land tax records. All of this gave me a much clearer image of the various Williamses living in Powhatan County, Virginia during the 1800s.

But there has remained this one problem: I still don’t know the identity of Joseph Williams’ father! So how do I make my staring-intently-at-the-brick-wall sessions more productive? What can I do besides wait for new DNA results to appear...or hope for a moment of genius to come over me?

1. Look at what you already know

The first thing we want to do when looking at a problem we can't solve is to determine what you already know. Establish that first.

So in my case, what do I know already about Joseph Williams? I know that he was born about 1817 or 1818, probably in Powhatan County (based on the 1860 census). If he wasn’t born in Powhatan County, he lived there at least since 1838 when he first pays personal property taxes and marries Ona Ann Adams.

And though we have no explicit evidence about the parentage for Joseph Williams, there is some reason to suspect John Williams may be his father. As I wrote in my blog, Why Genealogists Ought to Love Taxes:

From 1832 - when the tax lists began listing numbers of men over 16 - until John Williams last appears in 1837, there are only four white Williams men listed by name in Powhatan County: John, George W, Henry, and James H Williams. Only John Williams lists more than one white male over 16 years of age during that time period, and he does so beginning in 1834.

Though no record states explicitly the name of Joseph’s father, there are other contemporaries of Joseph who do list their father as a John Williams. James H. Williams, at the time of his second marriage to Pauline Utley, lists his father as a John Williams. This James H. Williams – in both this marriage record and in census records – is recorded as being born in Amelia County. Lucy Williams, the daughter of John Williams, marries John Adams in 1832. John Adams was the brother of Ona Ann, the wife of Joseph Williams. John Williams, the son of John Williams married Martha Maxey in 1826 in Powhatan County. Are they all the children of the same John Williams?

And then there’s also what we can glean from autosomal DNA results. There are numerous descendants of James H. Williams who match several known descendants of Joseph Williams along with many of their known shared matches. So far, there haven’t been any other connections identified between these matches except for their descent from these two Williams men. Many of the shared matches between these two groups are also individuals descended from the Utley family from Goochland. James H. Williams married an Utley. Several Williams men married Utley women in Goochland in the early 1800s as well.

2. Y-DNA work

Since I first wrote about my Joseph Williams Y-DNA mystery nearly a year and a half ago, a few more people have Y-DNA tested. And though my wall has not been broken down, I have reason to believe it might start to crack a little bit!

Match

|

Earliest Known Ancestor

|

GD* at 37

|

GD at 67

|

GD at 111

|

Markers tested

|

Z. Williams

|

unknown

|

1

|

1

|

3

|

111

|

R. D. Williams

|

Aaron Williams 1770 SC

|

1

|

-

|

-

|

37

|

B. E. Williams

|

Joseph Williams 1817 Powhatan, VA

|

1

|

1

|

-

|

67

|

B. B. Williams

|

Powell Williams 1735 Goochland, VA

|

2

|

-

|

-

|

37

|

J. C. Blackwell

|

Jesse Blackwell 1745 Goochland, VA

|

2

|

-

|

-

|

37

|

C. L. Blackwell

|

Jesse Blackwell 1745 Goochland, VA

|

2

|

2

|

-

|

67

|

M. R. Blackwell

|

Jesse Blackwell 1745 Goochland, VA

|

2

|

2

|

-

|

67

|

*GD – genetic distance: number of mutations or differences between two test takers

Since first buying a 37 marker Y-DNA test, I upgraded my father’s Y-DNA test to a 67 and most recently to a 111 marker test. In doing so, it has given me more clarity as to how closely he actually matches his closest matches. Unfortunately, only 4 of his closest 7 matches at the 37 marker level have upgraded to 67 markers, and only one of those has tested all the way up to 111 markers. More frustrating still is that Z. Williams, his closest match at the 111 level, has not listed his earliest known ancestor.

The next match, R. D. Williams, is descended from Aaron Williams of Georgia who was born in South Carolina. Though this is nearly as frustrating in its distance from Powhatan County, Virginia, it was a relief to see a Williams match after so long of only seeing a hodge-podge of other surnames. B. E. Williams is my father’s second cousin; these Y-DNA results, along with sharing an expected amount of autosomal DNA between them confirms their descent from the same Williams man.

More recently, I contacted another Williams man, descended from Powell Williams. Powell Williams lived in both Powhatan and Goochland counties in the early 1800s and was a contemporary of Joseph Williams. I had kept my eye on his records, always curious how the two might be related. And happily, this descendant of Powell’s matches my father’s Y-DNA! Eureka!

The remaining three matches in the table, Blackwell men, all descend from Jesse Blackwell of Goochland County. But how do Jesse Blackwell, Joseph Williams, and Powell Williams connect?

3. Trip to Goochland Courthouse

Before heading to Goochland County – the county immediately north of Powhatan – I wanted to find as much as I could about Powell Williams. I found him in several chancery cases, confirming names of his siblings (Edward and Samuel), a son George W. Williams, and that his father was also named Powell Williams.

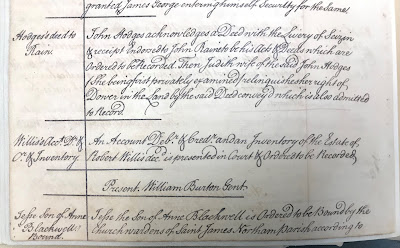

Descendants of Jesse Blackwell had told me that he was born out of wedlock to his mother Anne but I had never viewed his records at the courthouse. So I decided to view Jesse’s record myself, and see what I might also find out about Powell Williams, Sr. This took me to the order books for Goochland County.

So here we have the confirmation that Jesse was the son of Anne Blackwell. It doesn’t name his father. Was he born out of wedlock? Perhaps to a Williams man from Goochland?

“Ordered that the church wardens of St. James Northam Parish do bind Powel [sic] Williams an orphan boy unto Jeremiah Whitney a taylor [sic] according to law.” February Court 1744

Powell Williams was an orphan! But of whom?

These two records – from 1744 and 1755 – were both from St. James Northam Parish which falls in modern Goochland County. So we know that Jesse was born out of wedlock and Powell became an orphan in a similar time period. But how were they related? What's interesting is that Aaron Williams of Georgia had a son named Powell. Could it be a family name?

4. Orphans and Bastards

This is where I’m getting a tad more hopeful that I can find out more about our Powell Williams and Jesse Blackwell. They have slightly unusual names, and now they’re getting involved in the courts by being bound out. That means we have a paper trail, y’all! Paper trail means records!

But to understand any of the paper trail, we need to know how the law affected our story.

Early America – as with modern America – was concerned about who was going to have to take care of the poor. Is it on the state, the Church, or the common man? If a person was too poor to take care of their children, it would become the duty of the Church (later the State) to take care of the poor children. They would be bound out to someone who could teach them a trade, or at least teach them Christian faith and morals.

The laws concerning orphans and bastard cases evolved over time – beginning in the 1600s but come from English law. These laws include the punishment for a woman who has a bastard child (a child out of wedlock), and the punishment for a bastard child born from a black or mulatto man. Laws concern servant women who have children out of wedlock. There are laws for how often a guardian would need to report back to the county government regarding the property that was entrusted to them for the child bounded to them. There are laws for a lot of situations!

The wonderful Kelly McMahon Willette recently taught a session at the Virginia Beach Genealogical Society on working with cases of unknown parentage, specifically with bastard cases. What I learned that night - and what I'm super excited to put into action in my research - is to check the index in the order books for "presentment" or "grand jury." Often the orphans or bastards are not listed by name in the index. Pro tip from Kelly!

To read some of the laws yourself - especially relating the time before and immediately after our Jesse Blackwell and Powell Williams, you can search the Hening's Statutes at Large for Virginia Laws. Some worth perusing are the following: 1656, 1691, 1705, 1727, 1748, and 1769.

Here are some resources relating to orphans and the illegitimate:

- Orphans' Courts in Colonial Virginia - Evelyn McNeill Thomas

- The Difference: Apprenticed or bound out - Judy G. Russell

- Illegitimacy in the United States - the FamilySearch wiki

- Researching Orphan Children and Adoption in Your Genealogy - Sunny Jane Morton and Judy G. Russell

*****

My Williams mystery still eludes me. But I have made some progress by looking at what I already know, processing what I learned from updates to Y-DNA results, taking a trip to the courthouse, and by looking at Virginia laws relating to orphan and bastard cases. Genealogy is a process of continual education. As we research, as we process and write, we get greater clarity that can help us put cracks in our seemingly impossible brick walls.

What is keeping you from solving your "impossible" brick wall mystery? How might you make new discoveries if you take a look at your problem from a different perspective?

This post was inspired by the week 29 prompt "Challenging" of the 2019 series by Amy Johnson Crow's 52 Ancestors in 52 Weeks that I'm finishing up in 2020.

This post was inspired by the week 29 prompt "Challenging" of the 2019 series by Amy Johnson Crow's 52 Ancestors in 52 Weeks that I'm finishing up in 2020.

My ancestors - and your ancestors - deserve the best researcher, the most passionate story-teller, and the dignity of being remembered. So let's keep encountering our ancestors through family history and remembering the past made present today!

Photo by Victor Garcia on Unsplash